The Collective Bargaining Agreement: What is Negotiated?

By: Ken DeStefano

NOTE: This is the Third in a series of articles about collective bargaining in the NBA. We often hear about the NBA’s Collective Bargaining Agreement when issues arise with contracts, trades, lockouts, strikes, and player disciplinary proceedings. This series seeks to enhance the understanding of the CBA by providing context to the creation and implementation of the governing document between the NBA and the National Basketball Players Association.

What are the League and the Players Association allowed to bargain, and what will those proposals look like? Each party has done its survey, both formal and informal. They have reviewed the CBA, previous proposals, and grievances. That information gets inputted into a sophisticated algorithm, and concludes…the Players Association wants more money, and the League does not want to give it to them.

The League and the Players Association’s relationship is defined by federal law. That law places all negotiable items into one of three categories: Mandatory Subjects of Negotiation, Permissive Subjects of Negotiation, and Prohibited Subjects of Negotiation.

A mandatory subject is one that cannot be changed without negotiating. If an employer makes such a change, a union can file an unfair labor practice with the National Labor Relations Board. If a union makes a proposal about a mandatory subject, the employer cannot refuse to negotiate. Examples of mandatory subject are wages, grievance procedures, and health care.

A permissive subject is one that can be the subject of a proposal from either party, but the other party does not have to engage in negotiation. Typically, these relate to general business practices, or internal union or employer administration.

A prohibited subject is one that may not be the subject of negotiation. Neither side can make a proposal about a prohibited subject because enforcement of that provision would be illegal. These can involve criminal activity, or any federal law (for example, a provision that prohibits players from voting in a federal election).

Most negotiations will be about mandatory subjects, where the terms are divided into wages, hours and “terms and conditions.” The term “wages” is seemingly straightforward—Employer wants to pay worker $50,000, and Employee wants to get paid $60,000. There can be twists (Health insurance benefits? Retirement plans?), and we will discuss some of them below. The term “hours” refers to the length of the workday, or the work-year. “Terms and conditions” are often work rules, as well as more legalistic topics such as grievance procedure, no strike/no lock-out clauses, and the like.

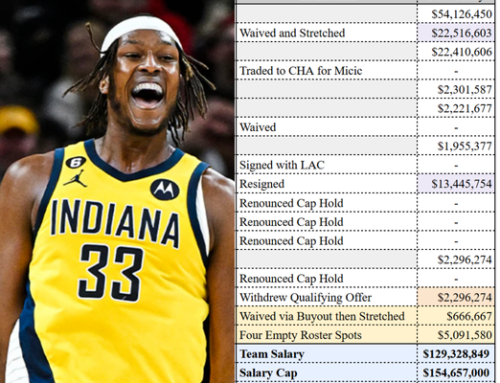

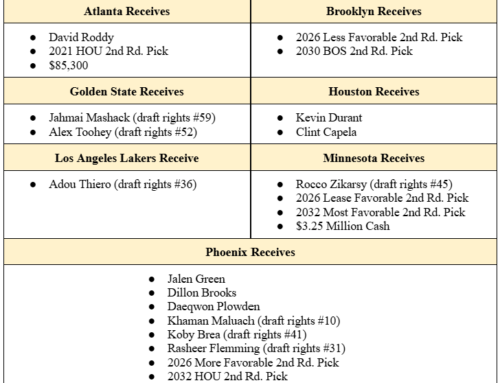

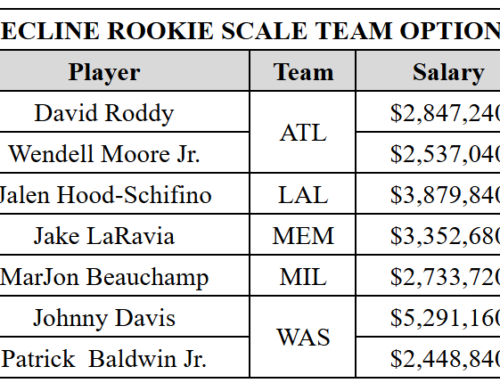

In the NBA, the Players Association does not negotiate individual player contracts—instead it negotiates the general pool of money that goes to players, and the ranges of salary and years that can be negotiated for each individual player. The free agent player’s individual salary is then negotiated between his agent and a team beginning on July 1 (not before—that would be tampering!!!).

For example, in the last CBA, the League and the Players Association agreed that the players would receive a percentage of forecasted revenues each year. Seems fairly simple—but it’s not, and it provides a beautiful example of how negotiation works. Under the current CBA, the players are guaranteed to receive between 49% and 51% of “forecasted revenues.” No doubt, the players want to receive more money, and the league wants them to get less. A Players Association proposal might suggest that in Year 1, the guaranteed percentage changes to 51%, Year 2 to 52%, Year 3 to 53%. The League proposal might suggest that in Year 1, it changes to 49%, Year 2 to 48% and Year 3 to 47%.

How does this get resolved? First, each party will have to assess what its real bottom line is. The Players Association might only want to get to 51.5%, but it may know (from previous dealing with the League), that it will have to start high, and walk backwards to its real number. Alternatively, the League might know that the Players Association does not inflate its proposals, and 53% is the real number. That’s the skill of knowing the other side.

Now that each side has winnowed the fat from proposals, we now see that the Players Association membership wants their negotiating team to “stay” at 50%, but the owners need the League to get below 50%. How to resolve this? Sometimes it can be done through a “phase-in.” For example, Years 1 and 2, it stays at 50%, and Year 3 it goes to 49%. Will this be acceptable to the players? Maybe not, so the Players Association may add a provision that says that in Year 3 the 50% will go to 49%, BUT IN NO EVENT will the dollar amount from Year 2 to Year 3 decrease. Will that be acceptable? Maybe. The negotiating teams must know their membership. Are there any other options? The parties can agree to change what is included in “forecasted revenues” so that the definition is more inclusive, so even a lower percentage will yield more dollars. To get a sense of how complicated this definition is (and thus subject to manipulation), see Question 15 of Larry Coon’s FAQ (http://www.cbafaq.com/salarycap.htm#Q15).

The next subject of negotiation—hours—is also a negotiation about money. The Players Association may want to reduce the length of the season by 5 games. The League might be sympathetic to the proposal, but…doing so will decrease regular revenue by just over 6% (5/82). Are the players willing to reduce their income by that amount? The Players Association may want to reduce the length of games to the college length (48 minutes to 40)—gate receipts won’t change, but venue concessions will decrease. Will the players accept this decrease?

How might this all get resolved? The parties could (theoretically) agree to a provision that keeps the schedule at 82 games, but entitles each player to 5 “personal days.” There would be the same number of games, so gate receipts would not decrease. Games would be the same length, so concessions would not decrease. But some fans might miss the chance to see their favorite players. If LeBron James decides to take his personal day against the Hornets, those fans would not have a chance to see a future Hall-of-Famer in person (because Western Conference teams only visit Eastern Conference teams once per year). The Hornets’ organization might lose an opportunity for an otherwise rare sell-out. The provision could be tweaked by prohibiting the use of a personal day at an away non-conference game. There could also be a provision mandating that the player has to list his personal day games before the season starts so ticket purchasers can plan accordingly. As always, the devil is in the details.

“Terms and conditions” negotiations can be particularly difficult because they are less tangible to the typical player or owner than other subjects. There is generally deference given to “ the lawyers”—until it’s not. A grievance gone bad, a clash on player discipline, a tweet about China—when these theoretical subjects become concrete, the parties can lock into emotional bargaining positions. Of course, these are the types of issues that could impact league revenue (about 10-20% of League revenue involves the China market), although not in a direct way like wages and hours. At these times, leadership can be particularly important in removing the emotion and coming to a resolution.

The parties have drafted their proposals, thought about the other side’s reactions and proposals, and are now ready to sit across the table. In the next article, we will discuss the across-the-table bargaining process.